The newest archetype taking the internet by storm is the image of the “Sephora 10 Year Old”, young girls who are trading in their toys for makeup, switching out their books for tripods, and experiencing their entire childhoods from behind the glow of smartphones.

The same platforms that sold them retinol serums and overpriced leggings have quickly turned against them. “Brainrot” has been coined as a term among younger generations, describing the adulterated condition of today’s youth at the hands of technology and social media culture.

It’s well known that infinite digitized stimulation hijacks young nervous systems to crave brainless, short form content that can instantly, and constantly, numb any ounce of boredom they feel. A publication by Harvard Medical School titled “Screen Time and the Brain” cites Pediatrician Michael Rich, saying, “Much of what happens on screen provides ‘impoverished’ stimulation of the developing brain compared to reality…A young person’s brain lacks a fully developed self-control system to help them with stopping this kind of obsessive behavior.”

The Society for Research in Child Development published an article in their flagship journal, “Child Development”, studying approximate consequences. They found “neurological diseases, physiological addiction, cognition, [and] sleep” to be relevant in considering negative effects of smartphones on developing children. At a purely biological basis, our culture’s irrevocable entanglement with our devices disrupts all of the natural, human rhythms our lives are meant to follow.

What experts are finding more alarming, however, are the behavioral effects that are sparked from constant exposure to social media. Chief Science Officer for the American Psychological Association Mitch Prinstein, PhD, formulated a written testimony for the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee on February 14th of 2023, dedicated to the topic of “online dangers” affecting modern adolescents. He attributes stark increases in depression rates, suicide, and even eating disorder emergency room admissions in recent years, (with some statistics doubling specifically in 2020…the height of the COVID-19 pandemic) as underscores of our society’s technology crisis.

Per widely accredited neuroscience research, Prinstein describes the period between puberty and early adulthood (approximately from 10-25 years old) as perhaps the most critical period for adaptive neural development. Prinstein also asserts that the onset of puberty, occurring during the same time, triggers a heightened desire for social rewards.

Social media is a highly accessible, and thus highly addictive form of fulfilling this crave for validation. However, it’s a form of validation that can’t offer the same substance and sustainability as true, healthy connections, effectively warping a dependent adolescent’s perception on realities of the social world. “In other words,” he says, “social media offers the ‘empty calories of social interaction’ that appear to help satiate our biological and psychological needs, but do not contain any of the healthy ingredients necessary to reap benefits”.

Misconstrued ideas about social truths are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Prinstein’s concerns about technology. The glamorization of disordered tendencies like suicide, eating disorders, and self harm, an increased likelihood for developing poor conflict resolution skills, heightened risk for negative peer influence, alterations in brain development, increased risk of bullying, harassment, and sexual exploitation, attention deficits due to “media multitasking”, isolation, and even just “digital stress” as a byproduct of constant engagement are all of the factors highlighted in Prinstein’s testimony…among countless others.

In addition to the literally neurodegenerative nature of constant engagement with social technology, a large proponent of the “Brainrot” phenomenon among children is the economy’s contemporary expansion to online spaces. Widely referred to as “the attention economy”, social media provides a powerful landscape for companies to control, measure, and generate attention as means of revenue. Simple actions like clicks, views, and likes have become as lucrative as actual purchases, although these new forms of attention capital are far easier to attain.

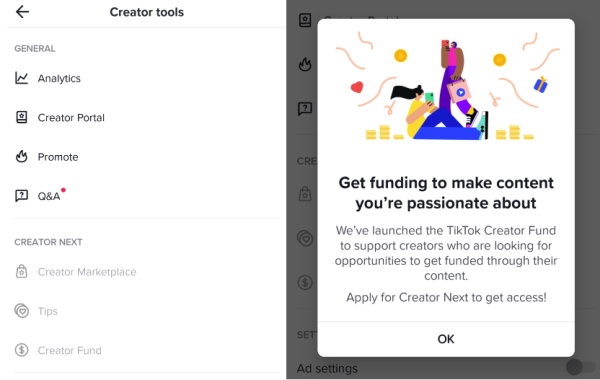

TikTok’s “Creativity Program” launched in 2023 replaced the original “Creator Fund” as means of “generat[ing] higher revenue potential” according to the company itself. TikTok claims that creators can earn up to 20 times the amount of money through the Creativity Program that they were making through the Creator Fund…some creators even reported earning up to $19,000 in just four months after being paid $0.50-$1 per 1,000 views on every video they post. This number might seem minuscule, although key metrics must be taken into account for reference. TikTok has over 1 billion active monthly users, most TikTok posts are only fifteen seconds long, and automatic replays are enabled for every user on the app.

In his book “Social Media & Capitalism: People, Communities, and Commodities”, author Sudduhabrata Deb Roy describes a common theme among the constantly growing, ever-engaging attention economy. In Chapter 3, he argues, “Social media commerce has made commodities more widely available in society, thus placing commodities and commodity fetishism at the center of society as a whole” (53). He concludes that social media itself is a commodity…one that also stimulates itself as a ruling mechanism for other methods of generating revenue by incentivizing consumerism. Various hosts of rapid trend cycles, the monetization of digital activity like messaging systems, and the exploitation of human inclination for fulfilling social needs are just a few examples Roy identifies.

The rise of the “Sephora 10 Year Olds” is being portrayed as concerning, unexpected, and even humorous. Many people, especially teens and young adults, are identifying problems with our digital culture for the first time thanks to this new trend.

“Brainrot” and the “Sephora 10 Year Olds” have met the same ironic fate as all of the trends that came before it. Their messages have shrunk into just another speck in the miserable circulation of recycled ideas, misinformation, and grasps for attention that comprise the internet. At the same time, exhausted kindergarten teachers prop up their iPhones to protest declining literacy rates among their students. Millions of posts criticizing overconsumption compete for the highest number of likes on TikTok. Older generations seem to be fully convinced that any Facebook post is entirely credible…especially the ones showcasing the devastating effects of social media on our children.